It’s an election year and too many times already I’ve heard “I don’t want to risk National getting in so even though I support the Green Party, I’m voting Labour”. It’s no surprise people think this because National have long been keen on confusing the public when it comes to MMP.

For example, National’s latest slogan calling a Labour/Green/Te Pāti Māori coalition - a “Coalition of Chaos” is no different to that 2014 (failed) election campaign they did with the waka (sorry National voters I mean ‘rowboat’) going around in circles - remember they got sued for it. Or the 2017 one with the runners all tripping over each other.

They’re always implying that any political party forming a coalition is bad news. This is despite the fact that they will have to form a coalition with misery goblin David Seymour and ACT.

National pushes the ‘MMP slash coalitions are bad’ barrow every year because National is the Ken Roy screaming “I’m the oldest boy!” of politics. They want to govern alone, compromising with nobody, and working with nobody.

But - the whole point of MMP is to give more diverse voices entry to parliament. So you can see why National with its ever changing leadership of bald white men who are indistinguishable from each other would be daunted by this. Diversity is scary to them - Hell they’re absolutely terrified of road signs with Te Reo on them.

But MMP is also confusing to a lot of people because it’s been a long time since we all went to high school and some of us were stoned the whole time. Not me. I would never do drugs.

So I decided to ask an expert.

Stephen Levine is a Professor of Political Science at Victoria University of Wellington and has published extensively on New Zealand’s politics, voting behaviour and electoral system.

He organises a post-election conference at Parliament (open to the public) following each New Zealand general election – the next one is scheduled for 6 December – with participation from party leaders, journalists and academics, offering perspectives on the election campaign and the outcome (including coalition negotiations).

His most recent post-election books were Stardust and Substance: The New Zealand General Election of 2017 and Politics in a Pandemic: Jacinda Ardern and New Zealand’s 2020 Election.

He’s the perfect person to teach us all about how MMP really works. So I got right into it with him:

Kia ora professor Levine! Thank you so much for sharing your time with us. I figured I’d ask the main question first. So let’s go: What exactly is MMP?

MMP – ‘mixed member proportional’ – is the name of the electoral system used to elect New Zealand’s members of Parliament. It was introduced for the first time at the 1996 elections after being approved by voters in referendums held in 1992 which was non-binding and 1993.

How does it differ from other ways of voting?

Democracies come in all shapes and sizes. The idea of democracy – ‘government by the consent of the governed’ – does not come with any one fixed way in which the people’s ‘consent’ is to be determined. As a result, democratic countries, wherever they are located, have developed many different ways – different systems – by which elections may be held. Traditionally, in New Zealand, from the first elections in 1853 through to 1993, voters in different communities elected an individual to represent them in Parliament. The winning candidate was the person winning more votes than any other, not necessarily a majority of those cast, a system known as first-past-the-post - a term having its origins in horse racing …

MMP is a mixed member system because some of the members of Parliament – MPs – continue to be elected as representatives of particular communities called electorates. Others, however, since 1996, are elected by having their names appear on a political party’s pre-election list of candidates.

Under New Zealand’s first-past-the-post system, voters were able to go into and out of a polling booth pretty quickly. They only had to cast one vote – for their local representative. Under MMP, however, voters now cast two votes: one, as before, for their preferred local MP and the other, the party vote, for their preferred political party.

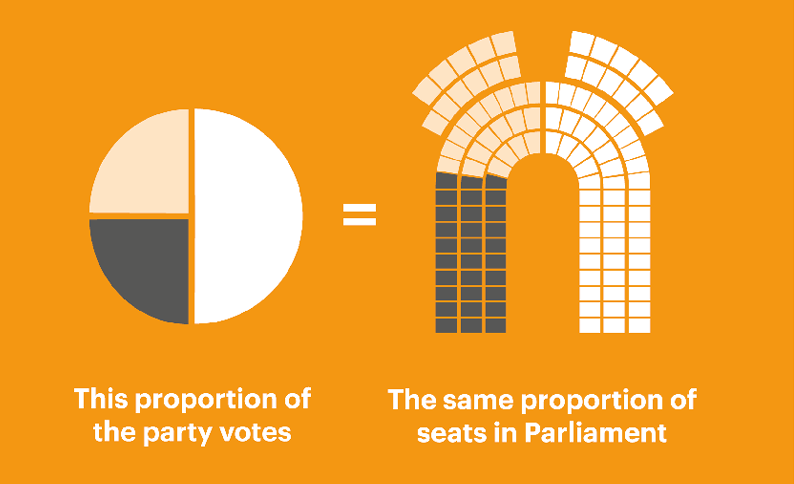

MMP is a proportional system because the number of MPs political parties succeed in electing to Parliament reflects – is in proportion to – the percentage of the party vote received by each party. A political party winning 5 per cent of the party vote, for example, is entitled to 5 per cent of the 120 seats in Parliament.

If I vote for a smaller party. Is it a wasted vote?

There are many views about what constitutes a wasted vote. For instance, it could be said that a vote has been ‘wasted’ when a political party or a politician, once in power, fails to do what they promised to do when campaigning for office. Indeed, the move to change New Zealand’s electoral system reflected voters’ frustration that successive governments in the 1980s and early 1990s, both Labour and National, had promised policies which they subsequently failed to implement – or had introduced policies they had never mentioned prior to the election.

If you could see my face right now lol

Broken promises led voters in the two referendums held on the electoral system to look for a way to punish the major parties for their behaviour. Voting for a new system, MMP, likely to bring smaller parties into Parliament, was one way to do so, curtailing the power of the country’s two major parties to do whatever they liked once in office. That, in any case, was the idea.

Is my vote ever a wasted vote?

As noted, a vote can be considered wasted if it produces results – policies, leaders, outcomes – contrary to what the voter intended to achieve. Of course, it’s not always possible to predict future circumstances. Jacinda Ardern had no idea, when leading Labour to power in 2017, that a terrorist attack would be launched on mosques in Christchurch, or that a pandemic would sweep across the world, bringing challenges to New Zealanders and those responsible for their welfare and well-being. On the other hand, New Zealand’s parliamentary elections are held every three years – a fairly frequent time period – which gives voters ample opportunity to decide whether a government and its prime minister should be rewarded with a further three year term or replaced by a seemingly more attractive alternative.

Under MMP a ‘wasted vote’ would be one cast for a political party receiving less than 5 per cent of the vote. A political party winning, say, 4 per cent of the vote – four votes out of every hundred – would not win any seats in Parliament. There is an exception to the 5 per cent party vote requirement: a political party winning at least one of the electorate seats, which are still held under first-past-the-post rules, would be entitled to additional seats even if their party vote is less than 5 per cent.

It’s also possible to think of a wasted vote as one cast by a voter for a candidate or party whom they do not actually support. People may waste their vote by voting for someone they don’t actually prefer because they believe – usually from media coverage and opinion polls which, properly conducted, are often pretty accurate – that their candidate or party has little or no chance of winning. Voting for a party or candidate with prospects of success may therefore look more appealing. Nevertheless it can be seen as something of a wasted opportunity – failing to vote for the candidate or party whom the voter really wanted to win if only others felt the same way...

If I want to keep out a major party from election - is it dangerous to vote for a smaller party?

In New Zealand there have been, since 1935 when the first Labour government was elected, only two ‘major’ parties: National and Labour. These two parties have been represented in Parliament, in substantial numbers, following every election held during the 1935-2020 period. Even when one of these two parties fails to become the government, its leader is the one known in Parliament as the Leader of the Opposition.

Realistically, then, it is the safest of all predictions to declare, in advance of 14 October’s election, that both of these parties will be well represented in the Parliament being elected on that date.

Votes for smaller parties are less predictable. Even so, most commentators would consider both ACT and the Green Party to be likely participants in the next Parliament, winning more than 5 per cent of the party vote and possibly, in each case, having one of its candidates win an electorate seat. Other parties – including New Zealand First, The Opportunities Party, the Māori Party / Te Pāti Māori – have less certain prospects, with the latter, competitive in several of the seven Māori electorates, the most plausibly confident.

Voters can try to predict whether their vote for a particular party may – or may not – affect another party’s chances of returning to Parliament or becoming part of the next government. A person choosing not to vote for a smaller party whom they actually support may well damage that party’s chance of electing any MPs. Choosing to vote for a preferred smaller party, on the other hand, may influence, or even determine, the composition of the next government – which parties are in it, which parties are not – depending on the overall election result and whether that smaller party is elected to Parliament.

Should we be afraid of coalitions? It feels like political leaders in major parties push us to only vote for major parties to avoid coalitions.

Of course it’s possible to be ‘afraid of coalitions’ when the referendums on the electoral system were held, those against change – opposed to MMP – warned that the result would be ‘coalition governments’, characterised as ‘unstable’, with the country’s major parties at the mercy of smaller parties with relatively little support. New Zealanders had been used to single-party governments: one party (Labour or National) forming the government, that party’s leader as Prime Minister, the other party in opposition. After MMP won and was introduced, predictions that coalition governments would be the outcome – no party winning a majority – were largely confirmed. Every MMP election beginning with 1996 and continuing until 2017 produced a coalition government: that is, no political party, neither Labour nor National, won a majority of the seats in Parliament. In every case, the post-election aftermath involved negotiations, leading – sometimes quickly, sometimes not – to a government in which more than one party was represented: a coalition.

This was actually MMP as it was intended to work.

In New Zealand, there are few of the checks and balances on a government – a Cabinet – determined to introduce and implement its policies and programmes. Born of frustration with both major parties, MMP was intended to limit their power, requiring them to share power with coalition partners – smaller parties unable to win power on their own, but present in sufficient numbers in Parliament so as to be needed to form a government.

The 2020 election was an exception, almost certain – another safe prediction – not to be repeated in October 2023. Buoyed in large part by its handling of the Covid-19 pandemic – keeping New Zealanders safe and alive in proportions not found or approached in other ‘developed’ countries – the Labour Party became the first political party to win a parliamentary majority, more than 50 per cent of the 120 seats in Parliament, since the introduction of MMP.

The election campaign that lies ahead will find party leaders and parliamentary candidates doing their utmost to win the most votes possible for themselves and their parties. At the same time, every party recognises that, this time around, the result is almost certainly to be a coalition. What we must hope for, ultimately, is that whichever coalition is formed – whichever parties choose to work together, developing their overall policy programme, allocating their ministerial positions – it will be one that keeps its promises, its participants characterised by integrity, character and good judgment: an outcome much to be preferred, but one that, on its own, no electoral system can ever altogether guarantee.

Thank you so much Professor Levine!

I’ve heard ‘the giant thumb’ say “coalition of chaos” so many times. I just want *ONE* journalist to ask, “Mr. Luxton, you’re clearly against coalition governments. Can you, today, rule out forming a coalition government if you receive the majority vote?” I’d love to watch the mental gymnastics required to answer when *HE* needs a coalition to govern.

Thanks, this is really helpfully written!