Welcome to the Sunday Essay. This will be an occasional series where when I have the funds I pay a writer I adore to write an essay about a topic that matters to them.

Your subscription gives me a chance to share the love and bring important writing into the world that might not otherwise exist.

Today’s essay is by the incredible Marianne Elliott. Marianne has worked as a human rights officer in the UN mission to Afghanistan and with the New Zealand and Timor-Leste governments. She is the author of Zen Under Fire: A Story of Love and Work in Afghanistan, and the co-founder of Action Station and co-director of The Workshop. She’s a mum and a fiercely kind friend.

Grab a cuppa and enjoy 💜

Running is more than exercise for me. I was one of the only kids in my school who looked forward to cross country. In my early twenties I ran the rural roads around my parents’ farm crying about my divorce. Later in my twenties I ran through dusty refugee camps in the Gaza Strip and in heavy monsoon rains in Timor Leste. Later still, I ran in hundreds of tiny circles around our walled compound in the mountains of Afghanistan, listening to Tina Turner and the Weepies. I run because it seems to help keep my thoughts and emotions moving, especially the dark, heavy or spikey ones. I get less stuck when I can run.

As a middle-aged white woman living in Wellington, the fact that I love to run is probably one of the more predictable things about me. But while there are enough of us on the trails and pavements of Wellington to make my half marathon training plan and the collection of trail shoes at my front door a cliche, the history of our exclusion from the sport is recent. Recent enough that one of the pioneers of women’s long distance running, Kathrine Switzer, is still running in Wellington today.

In 1967, Switzer was the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon, an athletic feat that people (even Switzer’s own running coach) had previously insisted was too demanding for the fragile female body. A few miles into her race, she was repeatedly assaulted by one of the race officials who yelled, “Get the hell out of my race” and tried to rip off her bib number. Nevertheless, she persisted, completing the race in 4 hours and 20 minutes. It was later confirmed she hadn’t broken any rules because the rule-makers apparently hadn’t thought to place any limits on gender. In response, the Amateur Athletic Union changed its rules to bar women from competing in races against men.

This past Saturday morning, I watched in admiration as Switzer - now 76 years old - ran around the Wellington waterfront in a local parkrun where I was volunteering. She later posted a photo of herself from the run on Instagram announcing she was “on the comeback trail”, which delighted me.

Parkrun is a free, weekly 5km event that takes place every Saturday morning at more than 2,000 locations across the world. While it’s timed, and many people use it as a measure of their running fitness, it’s non-competitive and designed to be inclusive. As well as welcoming walkers, wheelchair users, strollers and people of all ages, in 2019 “after careful consideration and extensive consultation” Parkrun organisers decided to continue categorising people based on gender rather than assigned sex, allowing “people to identify in the way they feel most appropriate and comfortable.”

Yes, I read the fine print on the parkrun website when I signed up, because I love running and I want this sport that I love to be as inclusive and welcoming as possible. I’m still learning what it means, and what it takes, to make running welcoming to everyone who wants to run. And the knowledge that 50 years ago I would have been banned from many of the spaces and races I now run in motivates me to help create running spaces that are genuinely welcoming to all.

On Saturday evening, a story popped into my Facebook feed about a transgender woman who was being attacked for running in the London marathon. Glenique Frank is 54, just a few years older than me, and she finished the marathon in 4 hrs 11 mins and 28 secs. A solid effort, and one she should be very proud of, but far behind the elite women runners, placing her 6,159th in the women’s race.

Like Switzer, Frank hadn’t broken any rules by entering the race. But not because nobody had thought to create any. There are rules governing the participation of transgender runners at the elite and competitive level of the sport. But, as London Marathon event director Hugh Brasher clarified last week, while the elite races at the marathon were subject to these rules, the mass event in which Frank participated was not. The London Marathon, Brasher said in an official comment, is “a unique celebration of inclusivity and humanity,” that “champions inclusivity” and they stand behind Frank’s participation in the female category.

When a transgender woman running in accordance with the rules in a public event is met with so much criticism and vitriol that she offers to return her participation medal, we see how regulations covering a minority of elite athletes have the potential to trickle down to create real life harm at all other levels of our sport.

I should know better than to read the comments, but I naively expected the post about Glenique Frank on Facebook to be inundated with comments from other runners cheering her on for her achievement. Instead I found hundreds of comments invoking the history of women’s exclusion from the marathon as a reason to be mad at Frank, claiming that her achievement had taken something away from all the other women who ran in the race. A classic ‘zero sum game’ narrative, to divide (and conquer).

A comment invoking the women who placed after Frank in the marathon as an argument against her participation pissed me off. Telling one group of people who have historically been excluded from a space that their hard earned right to be there is under attack by the next group of people fighting for access is as transparent as it is shitty. Shitty but also strategic, because solidarity is powerful and nothing undermines solidarity faster than scapegoating.

It also felt personal. I wasn’t one of the 14,000 women who finished behind Glenique Frank in London. But I’ve been one of them before, all those mid and rear pack runners in a major event, and I probably will be again. I don’t want anyone to use me as an excuse to exclude a transgender woman from an event I’m running in, even if she’s faster than me.

I run because running as fast as I can down a hill wakes up a part of me that remembers what it is like to be seven years old. I run because running hard reminds me that I can do hard things, and that lots of things only get easier if you keep doing them. I run because running quietly along a river or through a beautiful piece of bush is as calming and nourishing as anything I’ve ever done. I run because running with people is a wonderful way to talk to them, and a fast track to getting to know them. Yesterday I strapped my kid into the stroller and went out for a run because I knew I’d be a less cranky parent after a run.

I also enjoy competing. Anyone who knows me well will tell you I have a deeply competitive streak. They may also tell you it’s a good thing I have running to get most of it out of my system. I enter dozens of races every year. Depending on the race, I might train for months in preparation and I go into every race with a goal. Bettering my own previous best times, beating a runner I know to be at a similar level to me - it’s very satisfying.

I do enter running events with a goal time in mind, and work hard to meet that goal. I might even have a personal best time to beat, in which case every second counts. Once in a very small field I later realised that the runner who passed me while I peed on the side of the trail on the final downhill went on to take 3rd place in our age category, so the next year I just peed myself as I ran. But I’m generally not running to win, or even place.

I’m not telling you this because it’s unique or even particularly interesting. Hopefully we all find the things that help us get through life as best we can. Running is not going to be it for everyone, but it is for enough of us that you’ve probably read or heard something very similar to this before. I’m telling you this because I want to convey how much running means to me. I’m not an elite runner. Running is not how I make my living. But other than my family, friends and my work, it is probably one of the most important things in my life. Many of my closest friends are people I run with, or people I have run with over the years. I care deeply about running, and I’m genuinely grateful to women like Kathrine Switzer and many others who did hard things so that running spaces were more open to people like me. I will not be frightened into closing the door behind me.

I run because I love it and it does me so many kinds of good. But it gets a lot harder for me to love it and get that good out of it when I see other people being attacked for simply doing this thing that we both love.

I want our sport to do better. I want us to think about how we create running communities, spaces and events that are genuinely inclusive. I want us to ask people who don’t currently feel welcomed into those communities and events what needs to change and I want us to listen if they are kind enough to tell us. Because whatever aspirations runners may genuinely have for our sport, running is not, and has never been, equally welcoming to all kinds of people.

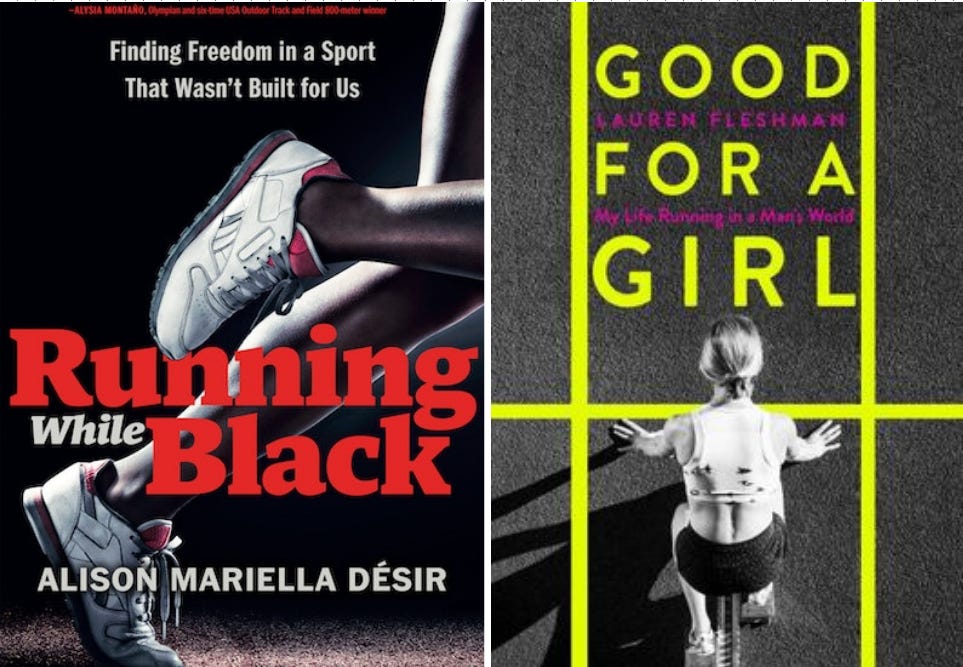

In her recent book, ‘Running While Black’, endurance runner and activist Alison Désir describes how the sport of running has largely been built with white people in mind and explores the many ways in which “the seemingly simple, human act of running for exercise and health has never been truly open to Black people.”

In January this year Lauren Fleshman’s memoir ‘Good for a Girl: A Woman Running in a Man’s World’ hit the New York Time’s best seller list in its first week, proving to the publishing world that the many millions of women runners around the world could also read. In it Fleshman writes about the impact of Title IX - a 1972 amendment to education law in the US which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation and gender identity) in any education program or activity getting funding from the federal government.

“Title IX opened a door fifty years ago that can never be closed again, but equality doesn’t end at the equal right to play. True equality in sports, like any other industry, requires rebuilding the systems so there’s an equal chance to thrive.”

― Lauren Fleshman, Good for a Girl: A Woman Running in a Man's World

I’m here for rebuilding all our systems so everyone has an equal chance to thrive. The systems that support, control and shape our running communities and events are probably not the top of everyone’s list when it comes to system change for justice. But running does matter, to lots and lots of us, and rebuilding these systems feels more achievable than some of the others I spend my days researching.

So here I am, reading the fine print about gender identity on the parkrun website and writing to celebrate Glenique Frank’s achievement at the London Marathon instead of going out for my own speed training session this week. It’s not enough. Just as showing up in Civic Square with our signs a few weeks ago wasn’t enough to prevent the transgender people we know and love experiencing new levels of hatred and attack. "But I know that those of us who just want to say ‘I see you, I salute you and I celebrate you’ need to show up and speak up, even if we’re midpack runners and haven’t written anything for other people to read for a long time."

That’s one inspiring piece. I love to run- even if sometimes just finishing is the best part. What a timely reminder to be mindful of holding the door open for others because it was opened for us ❤️

What a brilliant piece - thank you Marianne, and thank you Emily. Most inspiring thing I've read all weekend ❤️