What are the main concerns about the Covid 19 vaccines?

I talked to an expert to get the answers to all of the questions floating around...

I’ve seen a lot of talk on social on the concerns people have about the Covid 19 vaccine. I’m lucky enough to have access to experts a lot of the time through my work. I think it’s important everyone has that access. But obviously, that’s pretty hard when there’s so many questions and so few experts!

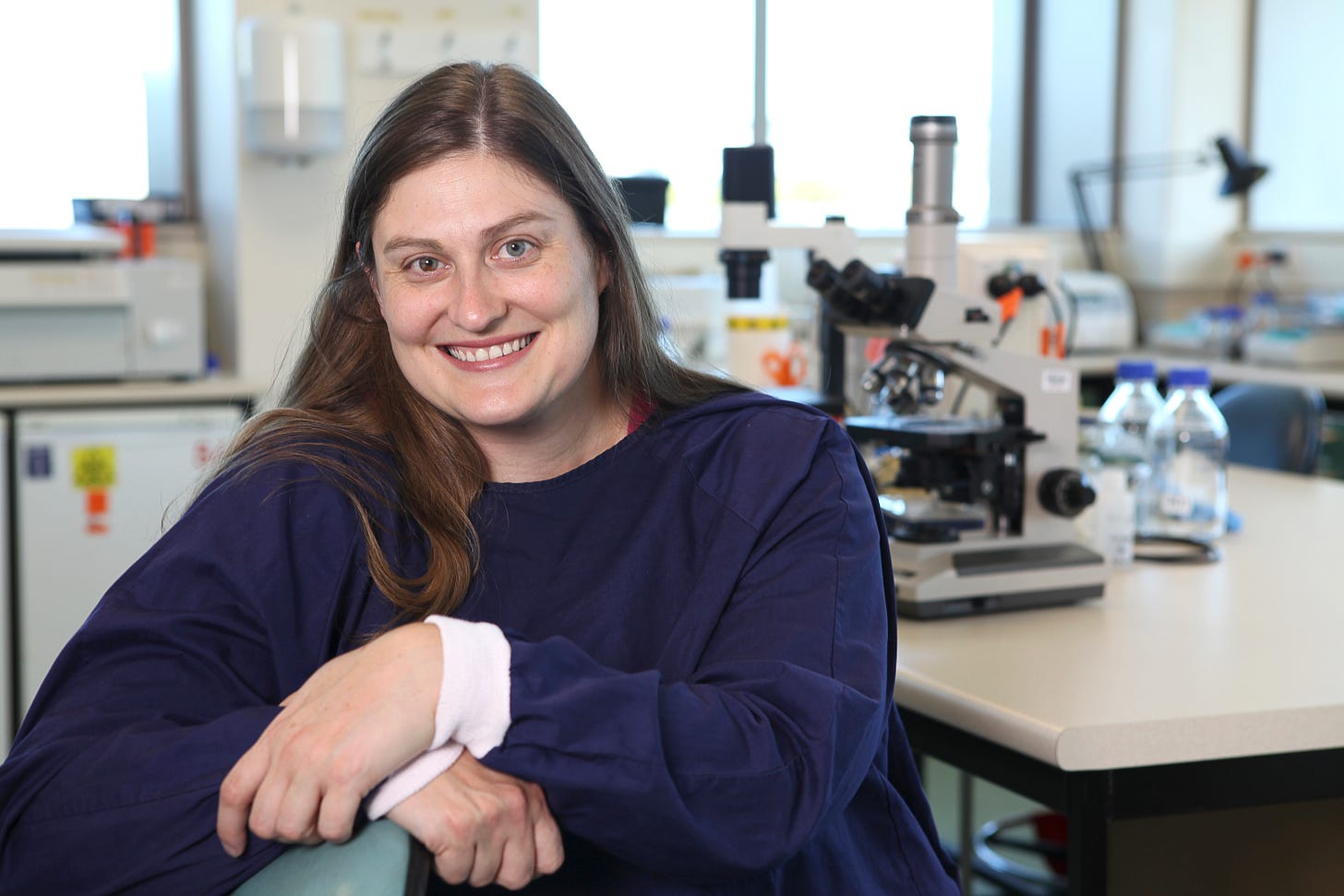

I am grateful that Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology at the

University of Otago Jo Kirman took the time to answer questions for me and you.

Please take her answers and share them with the world. We need to combat the misinformation out there with objection fact. This is part of my series on vaccines and I thank you for your support.

Thank you so much for taking the time to provide more information about the vaccine Jo. There’s a lot of nervous people so I really appreciate it.

Associate Professor of Microbiology and Immunology Jo Kirman

Emily: I thought I’d just ask for clarification on some of the major concerns I’ve been sent from people. But I’d love to start off by asking you why you got involved with researching vaccines in the first place?

Jo: I’ve always loved science and biology in particular. I went to Otago Uni to do medicine, but because of a slow recovery from a surgery (I’d been run over by a boat so had a propeller-ed foot!) I ended up unable to attend lectures and my first year at university was not a great success. So I studied Biochemistry and then after I’d had a few immunology lectures and absolutely loved it, I switched over to do an Honours degree in Microbiology & Immunology. I did very well, probably because I enjoyed it so much, and decided to continue with immunology rather than medicine. I love immunology because you can look under a microscope and see the soldier cells (white blood cells) get activated because they change from nice and round into wild and crazy shapes. You can measure what they do, making antibodies which can bind and inactivate viruses or bacteria or making chemical signals that attract other cells. You can even measure killer lymphocytes making other infected cells die.

I started off studying the Tuberculosis (TB) vaccine, called BCG, but I’ve also researched vaccines for other diseases like Leishmania (a tropical disease spread by a sandfly), HIV and influenza. The BCG vaccine is over a hundred years old, and it only works in about 50% of cases, so we need a better vaccine and that has been my research aim. Until COVID-19, TB killed more people every year than any other disease caused by a single infectious agent. It’s pretty sobering numbers.

Emily: Wow, I had no idea that was the case. Is that because of a lack of drive to improve the efficacy of the BCG?

Actually there’s a huge drive in the scientific community to improve BCG – I am one of thousands of scientists working around the globe on this problem. TB is much, much trickier than COVID-19 when it comes to vaccination because it needs a different type of immune response to fight it than a virus does. That immune response is much more challenging to induce through vaccination. But don’t get me wrong – the BCG vaccine is still an amazing thing, and not only can it prevent some cases of TB, but it can prevent and treat other completely unrelated diseases. For example, did you know that BCG is the standard treatment for non-invasive bladder cancer?

We Be Darker Than Blue Chip Thomas & Jess X Snow

Emily: That’s amazing! I did not know that. Let’s talk about the Covid 19 vaccines – there’s more than one correct? The Pfizer one and the Moderna one? How similar are these two vaccines and do we know which one we will get?

Jo: There’s even more than just Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines – those two are very similar actually – both mRNA vaccines, but the Moderna vaccine has an oily “coating” that allows it to stay active for longer at warmer temperatures (when I say warmer it’s still pretty cold – think -20˚C vs -70˚C storage). But -20˚C is a lot easier to transport than something that needs to be kept at -70˚C. You need special freezers to achieve -70˚C. So, the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine is perhaps better suited for mass vaccinations, for example, at hospitals than vaccinations given at a doctor’s surgery.

To explain what mRNA is: Think of our bodies as being built up from tiny Lego pieces (called cells). Each cell is a living thing and it has a function. For example, to make a hair, or to absorb food from your gut, or in the case of some immune cells, to make antibodies. Each cell has the same genetic blueprint (your genes) and this is called DNA. To do their different jobs, each cell has to turn specific genes from the DNA into proteins that help the cell do their job. To make a gene into a protein you need a transient intermediary and that is what mRNA is. It never lasts long, but it provides the “script” based on your DNA for the protein. So, with mRNA vaccines we are giving our cells a little bit of the coronavirus spike protein “script” so our cells can manufacture it by themselves. The mRNA doesn’t last long in your cells and it also doesn’t change your own genetic blueprint because it is not DNA. It’s just a temporary script that allows your cells to make a bit of spike protein. Then your immune cells take notice – they recognise the spike protein as “non-self” and start to make an immune response against it. Your B cells will make antibodies, and these antibodies can inactivate the virus if you get infected, so this makes you immune. The very cool thing about the immune system is that it can remember for years, decades even. So, your B cells that make antibodies can still react and make antibodies several years down the track.

As well as these vaccines, some other leaders are the AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson virus-vector based vaccines. These are based on adenoviruses which are missing genes that allow them to replicate, so they’re like virus-bodies that can’t reproduce and can’t cause disease. They also include the spike protein from the virus that causes COVID-19, so you make an immune response against spike. These vaccines have a slightly reduced efficacy compared to the mRNA ones, but they’re easier and cheaper to manufacture, and they induce strong T cell responses as well as B cell responses so they may be more durable over the long term.

There are also a few other types of different vaccines being used overseas, but for now, they are unlikely to be used in New Zealand.

Emily: Why is there more than one vaccine? Is one vaccine better than the other?

Jo: Simply put, there was a huge international effort to make a vaccine. Resources have been diverted (for example, many of my TB research colleagues have paused their TB research to work on COVID-19), and this work has been prioritised. The front-runners (from the dozens of vaccines being developed) had been in development for some time, so the concept of mRNA vaccines and adenovirus-based vaccines wasn’t new. Also, since the SARS and MERS outbreaks, a lot of research had been conducted on coronavirus vaccines, so there was a decade of research to draw on. But nobody would want to put all of your eggs in one basket. It was very sensible to work on multiple vaccine types. It has the benefit now, that we have several manufacturers to draw from and this enhances distribution. In terms of one being better than the other – well the efficacy is different, but only slightly different, so you could say that the mRNA vaccines are more efficacious than the adenovirus-based vaccines, but it is quite marginal really. These front-runners have all been very impressive.

Emily: Can you explain how the vaccine works?

Jo: All vaccines work by showing your immune system a bit of the virus or bacterium that you’re trying to prevent. It shows a small part (in this case the spike protein) which is harmless and your immune response can tell it’s not part of you (so it’s non-self) and it starts to make an immune response. Usually, for viruses, that response is a B cell response and the B cells make little Y-shaped molecules called antibodies that can bind to the spike protein on the real virus (if you ever get infected). The antibodies can inactivate the virus, so the virus cannot infect your cells and can’t reproduce. This means you won’t get sick or you will just have a very mild illness, if you get infected after you’ve been vaccinated.

Emily: There has been a lot of talk about how it doesn’t stop the spread of Covid 19 but instead limits how long you have it? And this argument is being (wrongly) used to justify not having it.

Jo: It is true that there really isn’t much data about how much the vaccine will limit disease transmission. But it is very clear that the sickest people have the highest virus counts (titres) so if you have a mild illness you are far less likely to transmit the disease, if you do at all. There’s plenty of evidence to show that vaccines limit the spread of viral infections for viruses which we have vaccines for when enough people are vaccinated in a population (think measles, mumps etc), so it’s likely this will be the case for COVID-19 vaccines. It’s very important to understand absence of data does not equal absence of effect.

Emily: Why is it important that everyone who can get the vaccine gets it?

Jo: This is something I feel very passionate about. When I give my vaccine lectures, I show my students a picture of a baby girl who was born in Australia just one day after I gave birth to my own daughter. That little Australian girl only got to live to four weeks of age, because she died from a vaccine-preventable disease. My daughter is nearly a teenager.

We only start vaccinating babies at six weeks of age, when their immune systems have matured sufficiently. So that little girl had relied on the people around her to be vaccinated, so they would protect her. That’s what herd immunity through vaccination is. It’s generating sufficient immunity within a population so the infectious agent can no longer spread. (Disregard all of the herd immunity through infection nonsense that you may have read about by the plan “B” folk – that is a misuse of the term and it’s just infecting and killing people).

Unfortunately, someone unvaccinated had passed on the infection to the vulnerable baby girl and she died. There are so many vulnerable people, when we think about COVID-19, so apart from protecting yourself through vaccination - which is a good thing to do, getting vaccinated will protect others. That’s your aunt with high blood pressure, your mum with respiratory disease, your dad with autoimmunity. A little kid with cancer.

If you are able to, but decide not to get vaccinated, you are deciding that you are comfortable that your inaction could result in the death of someone else. Finally, it’s important to consider that while “only” 1% die, about 5% of infected people become critically unwell with COVID-19. These people all require ICU beds, and we have limited numbers of these. That means that ICU beds being used for people with other illnesses or accidents or post-operative care become unavailable. Additionally, many others with severe COVID-19 (an additional 5-10% of cases) require hospitalisation.

If just 1% of people in New Zealand became infected with COVID-19 simultaneously, that’s up to 5,000 people requiring a hospital bed and 2,500 others requiring ICU care. In April 2020, we had 358 ICU beds available in all of New Zealand, so you can see that existing infrastructure gets overwhelmed quickly. Others with non-COVID-19 related illnesses such as cancer or even a burst appendix may not get the level of care they would usually receive. That is why prevention by vaccination is so important.Young people die from COVID-19 too – not as often as the elderly, but they do die, even apparently otherwise well young people. Also, if you decide not to get vaccinated, and you get very ill, you will rely on doctors and nurses and other health care workers to place themselves at risk to help you. Vaccination is a way of showing that you care about others, as well as yourself.

We Are In This Together (Circle) Pete Railand

Emily: A lot of people have been concerned that these vaccines were developed quickly. Should people be alarmed by a vaccine being developed in 10 months?

Jo: I really understand this. It is different from the usual process, and it seems really weird at face value. But as I said before these vaccines were already under development before COVID-19 because of SARS and MERS epidemics, which had generated sufficient concern for people to start this research. Many of the vaccines were being developed for other infectious diseases and were ‘repurposed’. So, this wasn’t completely new stuff – the vaccines were pretty much ready to move into clinical trial within a few months because of that. The trials themselves have been fast-tracked – much of the red-tape was streamlined so they could get started quickly. The EMA and FDA already had processes available for prioritising certain types of drugs or vaccines in emergency situations.

So, they removed the bottlenecks, so that the testing and evaluation could take place quickly. It has still been evaluated carefully. Rather than being concerned, I’m delighted that this could happen so quickly. It’s been a massive, communal effort.

Emily: One of the things being pushed online is that past attempts at developing vaccines for coronaviruses have ended in failure as they do not make it past the animal testing phase due to something being called “Antibody Dependant Enhancement”. One of my readers felt concerned by a video which claimed these vaccines have been exempt from animal phase testing and have gone straight to humans. Could you comment on this?

Jo: Antibody dependent disease enhancement is a real thing, but it is not known to occur with the types of vaccines NZ is considering, it’s more been seen with inactivated virus vaccines. There has been no evidence of this in the clinical trials – and there have been sufficient vaccinated and exposed individuals to have detected this, if it was a problem.

The many different government bodies evaluating the data have independent experts who check carefully for this and any other risks associated with the vaccines. This is part of the usual evaluation process.

These vaccines have also gone through animal phase testing – just some have done this partly concurrently (in parallel) with the clinical evaluation rather than fully ahead of it (as part of the streamlining process).

Emily: A lot of people are saying the Covid 19 vaccines aren’t actually vaccines because they’re mRNA technology. There are fears that this type of technology is untested. Do you have those concerns?

Jo: As I mentioned earlier mRNA is very transient. It breaks down very fast at body temperature (that’s why those vaccines need to be in such cold storage). So, it’s not something that is going to hang around for long at all. Also we have lots of our own mRNA in every cell in our body. So it’s not something to be afraid of – you are literally teaming with mRNA all the time.

Emily: One of the key arguments I’ve seen is around “long-term side effects” of the vaccine. Folks believe that we don’t know what the long-term side effects will be. Do you think this concern is a reason not to take the vaccine?

Jo: Most known side effects of vaccines manifest very quickly: allergic reaction, injection site inflammation, fever, muscle aches etc. It’s true that the clinical studies so far have performed follow up over months, rather than years. But, based on what I know about all our other vaccines, and the very short-lived nature of mRNA, I don’t think there are is any need for concern about serious long-term side effects.

Emily: Do you think the push back we are seeing against the vaccine is usual for vaccines? It feels similar to the rollout of the HPV vaccine – people were worried about that vaccine too. It seems like human nature to be concerned about vaccination. But do you think that the lies around vaccination are getting worse?

Jo: COVID-19 has been horribly politicised. Also, social media unfortunately is a hotbed of misinformation and can limit your perspective.

When you don’t understand something, it’s easy to get caught up in the misinformation and inadvertently spread it. Some of the arguments seem pretty well reasoned if you take them at face value.

When I’ve spoken up about misinformation on social media, I’m often told to “do your research”, which is pretty funny, given I really do actual research in a lab that gets peer-reviewed and published (as opposed to the five minute google version).

If I have toothache, I go to my dentist, and I trust that my dentist’s education has given them sufficient expertise to fix my tooth. When my car breaks down, I take it to a mechanic. I’m not an expert in any of these things, and it would be arrogant of me to assume I was.

So, it is tough when people, who have read an article for 15 minutes and watched a 10 minute YouTube video, consider themselves experts and their opinion is as valid as yours (or more valid), when you have 25+ years of education and experience in the field. But this happens in the media too, in order to achieve ‘balance’ a vaccine researcher is often paired with an anti-vaxxer who has no credentials.

It gives validity to these arguments, which are most often unfounded. I think people get caught up in anecdotal evidence. It’s pretty compelling. For example you could say “My grandad had the COVID vaccine and two days later died from a stroke”. It’s tempting to make the vaccine the cause for stroke and conclude that the vaccine is bad, but grandad was 89 and strokes are quite common in that age group.

As a researcher you can compare the number of people having strokes in his age group who weren’t vaccinated, with those who were, you can see if there are any increases in stroke incidence over the whole population.

At an anecdotal level you can’t tell much at all. But when a lay person is reading something, an anecdote is much more relatable and has more impact than data and numbers. So my message, which is buried in there somewhere, is trust your experts. Let experts argue amongst themselves - we don’t always agree, but we are usually able to reach a consensus view.

Many Hands For Human Need Josh MacPhee

Emily: One of the main anti-vaxx arguments out there is that if you’re confident in the vaccine then you should not worry about other people not getting it, because the vaccine will protect you. We know that fundamentally this is a ridiculous argument – but can you explain in layman’s terms why it’s wrong so that it’s easier for readers to combat this argument online?

Jo: No vaccine is 100% effective. These vaccines are up to 95% effective, which means five in every 100 exposed vaccinated people will display symptoms of COVID-19 if they get infected. These five people could develop productive infection that might transmit the disease to their little cousin with immune-deficiency, or their brother recovering from a heart attack. Vaccines don’t stop disease transmission when taken in isolation, we need to vaccinate a high percentage of the population (~70-80%) to achieve herd immunity.

Just because vaccines are not 100% effective doesn’t mean they’re not great. No contraception is 100% effective, but most people who use it will agree it has been quite useful.

Emily: Will you be taking the vaccine? And would you advise others to take it?

Jo: Yes, gladly and without hesitation! Yes!

Emily: Finally, I really struggle with the anti-vaxx rhetoric online suggesting “99% of people are fine with Covid 19”. My views are that this is an ableist position and disregards the worth of those who have died from Covid 19. Do you have a view?

Jo: Yes, I agree with your view that this is very ableist and also a bit naïve. The case fatality varies from country to country but hovers around 1%, so 99% of people survive. But what does survival look like? It does not mean that 99% of people return to exactly as they were before they developed COVID-19.

Ever heard of the long-term damage COVID-19 can inflict? COVID-19 can leave a lot of disability behind. Young, otherwise healthy people have had strokes and have had to learn to talk and walk again, if they can; others are left with long-term respiratory damage or cardiac damage. Long-COVID is the reality for many at the moment.

And then we must consider those that die from COVID-19. If I have a disability that makes me more susceptible to COVID-19 am I to be considered expendable? Because I am old, am I no longer worthwhile protecting? Is this the kind of society we want to be? The old saying “there but for the grace of God go I” is so true. One day you can be completely healthy, the next day you can be diagnosed with cancer, or autoimmunity, or some other disability.

Finally, it’s important to consider that while “only” 1% die, about 5% of infected people, become critically unwell with COVID-19. These people all require ICU beds, and we have limited numbers of these. That means that ICU beds being used for people with other illnesses or accidents or post-operative care become unavailable. Additionally, many others with severe COVID-19 (an additional 5-10% of cases) require hospitalisation.

If just 1% of people in New Zealand became infected with COVID-19 simultaneously, that’s up to 5,000 people requiring a hospital bed and 2,500 others requiring ICU care. In April 2020, we had 358 ICU beds available in all of New Zealand, so you can see that existing infrastructure gets overwhelmed quickly. Others with non-COVID-19 related illnesses such as cancer or even a burst appendix may not get the level of care they would usually receive. That is why prevention by vaccination is so important.

I choose kindness, and caring – for myself and for others. Please vaccinate!

Emily: Thank you Jo. Thank you for your work and your dedication. I really appreciate it and I know many others do too.

Your Lifevest is Under Your Feet Roger Peet

Amazing work, Emily. Very good Q&A about why the vaccine is so important and super accessible to people who don't have 25+ years of immunology experience